(click here if you want to drop right into the definition of the rhizome),

Life is complex, interwoven, and intimately and intricately interconnected. It can be difficult to fully comprehend just how connected all things are to all other things and to imagine the potential and possibility that is hidden in the interaction of all that connected complexity. There are so many ideas of systems and ways of thinking and conceptualizing the nature of existence, but there is one that seems to hold it all together. That’s the rhizome.

In their groundbreaking work “A Thousand Plateaus” (1980), philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (D & G) introduced the concept of the rhizome – a radical rethinking of how we perceive and understand the world. In this article, I’ll explain who Deleuze and Guattari were, what the rhizome is , why the rhizomatic vision of the nature of reality and the world is so important, how it might relate to your own life, and finally the ways in which it is an adequate lens through which to view my work on the interspecies and multispecies relationships and understandings of the Covid19 Pandemic and the SarsCov2 virus, and what that might mean for the world.

First, Deleuze and Guattari

Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995) was a French philosopher and thinker who wrote extensively on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art. Some of his works include Anti-Oedipus (1972) (co-authored with Félix Guattari) and A Thousand Plateaus (also co-authored with Guattari). Deleuze drew from multiple disciplines and thinkers, had a background in studying Spinoza, Bergson, and Nietzsche, and developed original concepts like the rhizome, assemblages, becomings, and the body without organs, difference, and multiplicity. His ideas and interpretations butted heads with traditional Western philosophy, pushing back against the Western emphasis on identity, representation, and rigid categories.

Félix Guattari (1930-1992) was a French psychoanalyst, political activist, and philosopher best known for his work with Deleuze. Guattari was trained in psychoanalysis and philosophy, worked at the La Borde clinic, and developed institutional psychotherapy and schizoanalytic practices that rejected traditional psychoanalytic hierarchies.

I think it’s important to understand that Deleuze and Guattari were political activists and radical thinkers; they were involved in anti-capitalist struggles and experimental revolutionary organizations. They were obsessed with exploring new ways of understanding subjectivity, power, and resistance in the contemporary world. This makes what they had to say particularly useful and relevant to the field of anthropology and even more so to multispecies thought. It’s also important to understand that they are ridiculously hard to read. Their work is elusive, fluid, and moving and can simultaneously frustrate you and drop you into different ways of seeing and experiencing the world. For me, it’s like a wild hallucinogenic trip, and when I pick up the book and read, I never know whether the trip will leave me frustrated and anxious or one with the universe. There are endless insights, conversations, and terms that come up when reading Deleuze and Guattari, but I want to focus here on the rhizome.

So What’s a Rhizome

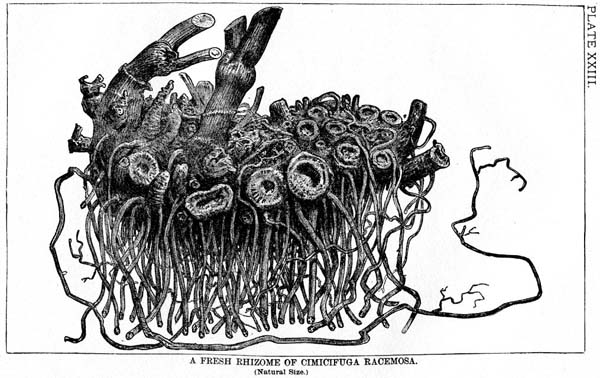

Imagine a sprawling root system, neither beginning nor ending at any fixed point, spreading horizontally beneath the earth. This is the rhizome. It’s a metaphor borrowed from botany to describe a non-linear, non-hierarchical mode of thinking and being. The rhizome offers a way of thinking about the world that emphasizes the interconnectedness of all things and works to envision the way that systems have the habit of evolving and escaping our attempts to categorize and control them. Deleuze and Guattari contrast the rhizome with the arborescent (tree-like) model of being. With its dominant trunk and descending branches, a tree can be likened to traditional, western, philosophical, and scientific thought in that it’s hierarchical (top-down). But the rhizomatic moves and functions horizontally, spread out, reaching, touching, connecting, combining, and transforming one point and any other at any given moment. There is no center, no top or dominant portion, and it does not have one way of being, seeing, doing, or experiencing because every portion of the rhizomatic spread has its own perspective, its own view, and place in the world. There is no hierarchy because all that is needed to thrive is to connect and ride along just underneath the surface.

Six Marks of a Rhizomatic Network

Deleuze and Guattari give us six identifying marks of the rhizomatic and I’ll list them below because I find these six ideas to be helpful in understanding the complexity and interconnectivity of the rhizomatic:

- Connectivity: In a rhizome, any point can be connected to any other point. There are no fixed paths or hierarchies.

- Heterogeneity: Difference. A rhizome is made up of diverse elements. It doesn’t matter if these elements are similar or different; they still connect.

- Multiplicity: A rhizome is not defined by the number of its parts but by what those parts can do. It’s about the potential for growth and change. Multiplicity is about a network of nodes that are interrelated but do not follow a strict hierarchical structure. It acknowledges that connections between points can take different forms and directions, and thinking of multiplicities in rhizomatic terms emphasizes the fluid, evolving, and non-hierarchical nature of relationships.

- Asignifying rupture: If a rhizome is broken or disrupted, it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines. It’s resilient and adaptable.

- Cartography: A rhizome is like a neverending, always in the act of becoming, map. It’s open to constant modifications.

- Decalcomania: A rhizome is not a tracing or a reproduction of something else. It’s its own thing, with its own logic.

You might be standing on a rhizomatic network

Imagine a patch of grass in your backyard. Each blade of grass is an individual, separate from the others, unique in its position and presentation to the world. But underground, all blades are interconnected by a complex network of roots and shoots, forming a rhizome. If you were to cut a piece of grass, it would simply grow back, often stronger than before. Like the grass, a rhizome has no central point or hierarchy (connectivity and heterogeneity), and its strength lies in its ability to continually connect, adapt, and grow in multiple directions (multiplicity). Even if a part of the rhizome is disrupted or broken, it can regenerate itself from any point (asignifying rupture). The rhizome is not a fixed, static structure but a dynamic, evolving system (cartography) constantly in the act of creating new connections and possibilities. Now imagine that the grass is the entirety of existence. Everything we know and don’t know. Everything we see and don’t see. By seeing reality and existence as a complex, interconnected rhizomatic network, everything from social movements to the spread of ideas and even pandemics like COVID-19 take on a different shape. We, as individuals, take on a different shape if we come to understand that we are unique, but connected. In an undetermined number of “steps” or “links” everything is connected and related to everything else. Kind of like Kevin Bacon.

Six Degrees of All Things

One of the ways I like to think about the rhizomatic is through The 6 Degrees of Kevin Bacon. While the “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” theory is specific to the interconnectedness of actors in the film industry (any actor can be connected to any other actor in 6 steps of connection), the idea of “six degrees of separation” has been applied more broadly to suggest that all people are connected to each other by no more than six social connections.

6 Degrees of Separation was an extension of a concept developed by the Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy in his 1929 short story “Chains,” which became the subject of academic research and popular interest because despite the vastness and wild diversity of the world’s population, we are all more closely connected than we might think. (In fact, it is my hypothesis that we are intimately and intricately connected, and I propose a “Six Degrees of All Things” theory that uses the principles of the rhizome to suggest that all things in the world (and by all things, I do mean -all-) are interconnected and that these connections can be traced through a relatively small number of “links” but that is a blog post for another day).

I’m not the first to think along these lines of course. One can find similar thought in theories like:

- Ecology and systems theory, which emphasize the interconnectedness of organisms and their environments.

- Quantum entanglement, which suggests that particles can remain connected even when separated by vast distances.

- Actor-Network Theory (ANT), which proposes that social phenomena are the result of complex networks of human and non-human actors.

- The Gaia Hypothesis, which suggests that the Earth’s living and non-living components are deeply interconnected and form a complex, self-regulating system.

- Donna Haraway’s “Naturecultures” that demonstrate the blurred boundaries between nature and culture.

- Tim Ingold’s “Social Becomings” which demonstrates that biology and social processes are so intertwined that they are what shapes beings and landscapes.

So, while a “Six Degrees of All Things” theory could start out playful, it might actually have some serious philosophical and scientific implications. But how can this help us to better understand viruses and pandemics?

Looking at the COVID-19 Pandemic through a Rhizomatic Lens

Since viruses and pandemics are the focus of my research, I want to unpack the complex, interconnected nature of the COVID-19 pandemic through a rhizomatic lens. The pandemic has revealed the almost unfathomable interconnectedness of our world (connectivity), with the SarsCov2 virus spreading through the intricate network of human and more-than-human interaction. Its linked an incalculable array of actors and elements into a rhizomatic web: viruses, humans, animals, governments, nations, economies, healthcare systems, and technologies etc have all been affected. This connectivity has also shaped social movements, influenced political outcomes, fueled authoritarianism, inspired rebellion and revolution, and fostered conspiracy theories that have taken on a rhizomatic nature all on their own. The pandemic has altered sensory perceptions, led to mass trauma, and driven inflation. It has intensified soul-shattering isolation and loneliness, deepened experiences of loss and grief, and exacerbated both intimate and structural violence against women. At the same time, it has exposed violence embedded in ecological relationships, extending from pangolins to wolves, from bacteria, fungi, and viruses to landscapes, weather patterns, and climate.

The Seen and the Unseen

I could write for hours about the layers upon layers of outcomes, effects, and changes the pandemic has ushered in, and these examples are only what we see! There are unseen dimensions of multispecies and interspecies relationships that we are just beginning to grasp through the rhizomatic lens. They reveal the interconnected nature of life (and nonlife) and the pandemic’s intimate, intricate, far-reaching effects. It hasn’t been all bad (because, rhizome!). There’s also been global collaborations in science on scales we haven’t previously seen, accelerations in digital transformations, and we’ve seen the importance of reimagining public health infrastructure to allow us to express morality and ethics within our current social systems. Yet, the pandemic has also shown that these systems—tethered to capitalism, globalization, borders, nations, and states—are deeply, deeply, d e e p l y flawed. It’s revealed in new ways that our current way of existing as a species is incredibly fragile for everyone involved, and that there might be better ways to be animal on this planet. It has pushed local and global communities to find new ways to stay connected, shown us what resilience and mutual aid can look like outside state systems (and the way it shines when we experience it!), and illuminated the world stage to show that solidarity, cooperation, and connection are key to counteracting oppression and violence.

Rethinking Everything

The Covid19 Pandemic has allowed us to rethink our relationships and priorities, inspired renewed focus on what it means to be mentally well, what work means, who performs the labor, and who reaps the benefits. And these connections I’m listing here primarily involve humans; the more-than-human world has its own beautiful, tragic, wild and different stories to tell. The pandemic’s impact cannot be reduced to just stats; it’s transformed the world in countless, unquantifiable ways (multiplicity). Despite the disruptions, societies, species, and individuals have adapted and innovated (asignifying rupture), and continue to adapt and innovate, continue to build new inside of what is crumbling or threatened.

Our understanding of the pandemic is constantly evolving (cartography), and while we can learn from past pandemics, COVID-19 presents unique challenges and consequences that we are still working to understand (decalcomania).

Rhizomatic Love Language

I hope you can see the way that I’m in love with the rhizome (and Deleuze and Guattari’s work). The way that I believe it holds a beautiful and apt framework to understand the intricate web of connections in our world. No matter where we apply it (philosophy, social systems, our own life in its mundanity, beauty, and tragedy, or global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic), the rhizomatic perspective helps reveal the underlying complexities and the resilient nature of interconnected systems. It challenges traditional hierarchical thinking, flips the Western narrative on its head, and it invites us to see the world as a shifting, changing, fluid, ever-forming, dynamic, evolving network that each one of us is a part of, where resilience and potential lie in the connections themselves. It is resilience and potential, the cracks in the wall, that are the openings to endless possibilities that I am most interested in, and I’ll talk more about that soon.

Take This With You

What I want to leave you with here is this: See the world as a rhizome. See yourself as node in this rhizomatic wonder. Watch the ways that interactions and connections shift and move your personal landscape. See your uniqueness, your contribution, and also see your insignificance. Holding both together allows for untold possibility. It allows for revolution, and rest. It allows a glimpse of the possibility and beauty that all of this (reaches arms wildly outward toward the entirety of existence) can hold.