On the curious case of conservative witchification of Taylor Swift.

“We don’t live in a patriarchy.” We hear this often, followed up with stats on women’s place in the corporate world, women in leadership positions, and often with all the ways society benefits women over men. Those of us who make it our business to study the social and cultural dynamics of power academically can follow up in response with definitions and examples, explaining patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism, but the reality is people are gonna see what they wanna see no matter the evidence. Because, you know, “haters gonna . . . “

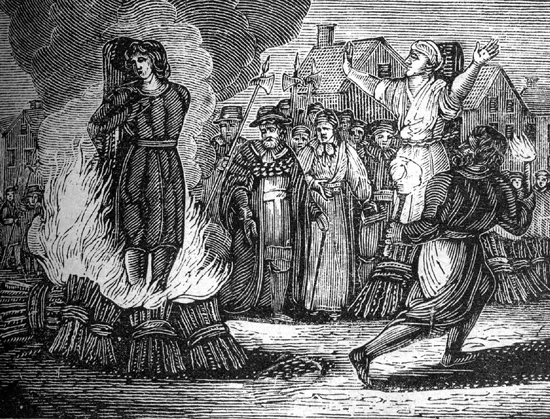

We’re not in a post-patriarchal anything, by the way. I, along with other theorists, have said for years that the witch trials never truly ended; they just look different now.

Let’s take for example the Trump campaign rhetoric of a “holy war” against Swift

Trump Allies Pledge ‘Holy War’ Against Taylor Swift/ Rolling Stone

Just a few hours old—doesn’t get more recent than that— and it is the perfect example. Because, at the outset, it looks like just another political skirmish, right? Just another tactic in the ongoing never ending ridiculousness of two party politics. But if we look a little closer, it’s got all the ingredients tossed into the bubbly cauldron of witchcraft for a modern-day witch trial. It might be cloaked in the rhetoric of political allegiance, but pull off that mask and the attempts at control and suppression that have targeted women for centuries? They’re exposed like the old man under the sheet complaining about meddling kids.

There’s still this idea that the witch trials were about ungodly women bound spiritually and sexually to satan casting spells and throwing hexes, but that was just the rhetorical vehicle used to control and suppress.

Labeling women as witches served as a tool of social and economic control during the upheaval that marked the long transition from feudalism to capitalism. Women who defied societal norms, who wielded influence or demanded independence, who owned property, benefited from the commons, were outspoken, spoke truth to power, who were young, beautiful, and sexually arousing, or who were aging and a nuisance to care for were often the targets.

Capitalism required the patriarchal domination and control of women to come into being, and it accused any who did not fall in line of witchcraft as a means to police behavior and reinforce emerging structures of power.

Fast forward to today: the tactics have evolved, but the essence is the same. The attack on Swift, under the guise of a “holy war,” mirrors the puritanical crusade, the insistence that the burning of women was a god-backed reclamation of moral righteousness, a necessary cleansing of evil and corruption, because:

“Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”

It was rooted not only in economics but in puritanical ideas of sexuality that still play out today. Enraged by their own lack of morality, men often blame the clothes, the appeal, the seduction, the allure, the enticement of women instead of self-reflecting. And women, deriving power from the men they are next to, often do the same.

Taylor Swift is being vilified not just because of her political beliefs but for her role as an influential woman who dares to speak her mind.

She has:

Influence.

Power.

Beauty.

Magnetism.

Talent.

Money.

She Persists.

She speaks back.

She calls out.

And all the while she rises and rises in fame and power in ways that should be praised with nationalistic, capitalistic pride. It’s a reminder that women who challenge the status quo, especially on the public stage, are a threat. Think of the way that men feel the need to tell women comedians that they aren’t funny, the way that women’s sports are only watched for fetishization value, the way that women in tech are constantly and continually harassed, the way that any woman in the political sphere is belittled, mocked, humiliated, hated, and threatened in the most vile and horrific of ways. The reality is that being anything other than compliant with patriarchal norms as a woman will see you to the pyre, or at least the pillory.

It reflects a continued societal impulse to police and punish women who wield significant influence, particularly those who challenge or critique established power dynamics. Swift’s potential political endorsement, her advocacy for women’s and LGBTQ rights, her pushback and win against sexual assault, and her outspoken criticism of Trump all put a target on her back. One can almost see the fingers pointing from the gallery with shouts of “Burn her!”

And the gallery is a reminder that the witch trials weren’t just court cases; they were public spectacles, lessons on a grand stage designed to isolate and denigrate, teaching everyone to watch their words, to silence their truths out of fear of becoming the next target.

Today, social media turns personal opinions into public spectacles. Magnifying voices of dissent and manufacturing outrage, drawing from a deep well of dissatisfaction—a yearning for a dream that never actually existed, a search for meaning in a faith that is somehow diluted and threatened by other religions, and a reaction to perceived constraints on speech that are often nothing more than calls for accountability.

The tactics of vilification and public shaming of women haven’t changed; they’ve just adapted. The intent remains the same: punish by example. ‘Watch your voice, or you’ll be next.’ This feeds on the discomfort some men feel in a world moving towards sharing power more equitably. And the discomfort some women feel at being a lesser object in a world of gendered objectification.

It’s not about losing status or control but a deep existential fear of sharing the spotlight, of making room at the table for voices long silenced, but it can justifiably feel like a loss to those unaccustomed to questioning their place in the social hierarchy. It’s about fear of irrelevance. Fear of dying without mattering (which is actually rooted in the hyperindividualism of patriarchy and capitalism, but I digress).

The reality is, under capitalism, we’re all irrelevant. None of us matter. The only way out of this existential crisis is through community, connection, belonging, solidarity, and sharing power.

Sharing power doesn’t diminish it; it multiplies it, magnifies connection, creates a richer, more diverse tapestry of human experience, a tapestry that, woven of community and belonging, can bear the weight of our fears. Can cover over ideas of irrelevance, of loneliness of isolation and, in the process, weave a world where, as the Zapatistas put it, “many worlds fit.”

But in the face of change, some want to cling to familiar narratives, finding solace in the flames of blame. The backlash against Taylor is part of the struggle to accept a world where influence and authority are no longer the exclusive domain of a few. It’s predominantly men who vilify her, revealing a resistance not just to Swift as an individual but to what she represents in a broader societal shift towards equality and empowerment.

Powerful women threaten everything. They always have, and they always will.

And it reveals the enduring presence of misogyny in public discourse. It reflects a broader societal discomfort with women who possess and exercise cultural, political, social, or economic power. The backlash Swift faces for her potential political involvement and her advocacy efforts highlight the ongoing struggle against patriarchal norms that seek to dictate the acceptable parameters of women’s participation in public and political life.

The rhetoric that has incited hoards of angry football fans to riot from their living room chairs is like any other rhetoric that is purposefully manufactured to target this demographic: easily palatable, tastes good going down, requires no chewing, soothes a digestive system irritated by ideas that forward a more equitable society and justifies and explains feelings of perceived persecution. That this particular spoon-fed rhetoric is so successful at the outset can seem nonsensical.

After all, Taylor is the epitome of the American Dream: hard work, sacrifice, and economic and social success. Her relationship with Kelce is traditional boy meets girl, masculine smiling football star and beautiful feminine blonde cheerleader; what could be more apple pie than that? Never mind that the relationship has upped viewership and increased the well-lined pockets of the NFL elite. How could any of this possibly be controversial? It should be the conservative wet dream.

But the reality is that anything that might answer the gnawing gripe of irrelevance and disappointment at one’s place in life is easy eating. Anything that promises a return to one’s youth, one’s vigor, one’s vitality (even if only in the imagination) is tasty going down. And it’s all the more palatable if it’s served by a woman who can be turned into a witch and burned at the pyre as a sacrifice to the lost promises and lack of hope of the American Dream.

For thousands of years, we’ve grappled with what to do with powerful women, using age-old tactics of intimidation and character assassination to silence their voices. The vilification of Swift is the modern-day witch hunt, and it reveals how deeply ingrained, easily manipulable, and wildly successful patriarchal mechanisms of control are still in our culture.

So, when we peel back the mask of political rhetoric and media spectacle, what remains is a clear and undeniable truth:

Yes, we still live in a patriarchy, where women’s voices, power, and influence are systematically challenged and suppressed. The battles fought by Swift and countless others are not just for personal vindication but are part of a larger struggle for gender equity and liberation from age-old oppressive norms. Recognizing this is the first step towards meaningful change and becomes a call to action to continue challenging the patriarchal-capitalist status quo, ensuring that the echoes of the witch trials truly become a thing of the past.